One step closer to a functional cure for diabetes

Dr. Timothy Kieffer, alongside a researcher from the Kieffer lab.

“We envision a future where people with type 1 diabetes can live their lives free from daily insulin injections and immune suppressing drugs. That future is now within reach.” – Dr. David Thompson

Clinical trials are the driving force behind medical progress, offering hope to patients, saving lives through innovative treatments, and propelling the boundaries of scientific knowledge.

The Stem Cell Network (SCN) sat down with Drs. David Thompson and Timothy Kieffer to discuss their groundbreaking research and clinical trial that is focused on using stem cell-based devices to find a functional cure for those living with type 1 diabetes.

What is Type 1 Diabetes?

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects more than 300,000 Canadians and costs the health care system approximately $29 billion annually. Those living with type 1 diabetes cannot produce insulin, an important hormone that helps the body control glucose levels in the blood. Although life saving, insulin injection is not a cure for diabetes. The positive news is that innovative stem cell therapies may be the best answer for future treatment and a functional cure – and some of the most advanced research is taking place right here, in Canada.

Canadians leading the way

“You don’t think much about your pancreas until it isn’t working,” said Dr. David Thompson, principal investigator at the Vancouver trial site, clinical professor of endocrinology at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and director of the Vancouver General Hospital Diabetes Centre. “But, when it comes to diabetes research, Canadians are leading the way. We discovered insulin, we proved the existence of stem cells, and now we’re using stem cells in clinical trials to hopefully one day eliminate the need for insulin injections.”

Funded in part by the Stem Cell Network, the multicenter clinical trial is for an experimental stem cell therapy developed by ViaCyte (acquired by Vertex Pharmaceuticals) that is being clinically tested in Canada at the Vancouver General Hospital, with additional sites in Belgium and the United States.

The therapy aims to replace the insulin-producing beta cells that people with type 1 diabetes lack. Dubbed VC-02, the small implant contains millions of lab-grown pancreatic islet cells, including beta cells, that originate from a line of pluripotent stem cells.

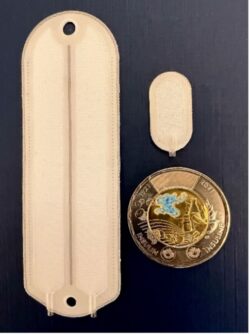

The implant device is shown alongside a smaller “sentinel” device. $2CDN coin commemorating the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin for scale.

The devices — approximately the size of a Band-Aid and no thicker than a credit card — are implanted just beneath a patient’s skin where it is hoped they will provide a steady, long-term regulated supply of self-sustaining insulin.

“Each device is like a miniature insulin-producing factory,” said Dr. Timothy Kieffer, professor within the departments of surgery and cellular and physiological sciences at UBC, the school of biomedical engineering, and past chief scientific officer of ViaCyte. “The pancreatic islet cells, grown from stem cells, are packaged into the device to essentially recreate the blood sugar regulating functions of a healthy pancreas.”

Promising results and a significant milestone

Over the course of 2023, the clinical trial enrolled and monitored 10 participants, each of whom had no detectable insulin production at the start of the study. All participants underwent surgery to receive up to 10 device implants each.

Dr. David Thompson meets with patients in his office.

Six months later, three participants showed significant markers of insulin production and maintained those levels throughout the remainder of the year-long study. These participants spent more time in an optimal blood glucose range and reduced their intake of externally administered insulin.

One participant, in particular, showed remarkable improvement, with time spent in the target blood glucose range increasing from 55 to 85 per cent, and a 44 per cent reduction in their daily insulin administration.

The results, which were published in Nature Biotechnology, mark a significant milestone for Drs. Thompson and Kieffer and their teams at Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) and the University of British Columbia.

“For the first time, we have shown that a stem-cell based device can reduce the amount of insulin required for some trial participants with type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. David Thompson. “With further refinement of this approach, it’s only a matter of time until we have a therapy that can eliminate the need for daily insulin injections entirely.”

The results of the clinical trial are the latest in a series of trials funded by the Stem Cell Network and conducted by the UBC-VCH team. Previously, in a 2021 study in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers were the first to show that the approach could produce insulin in the human body.

Stem cell generated islets made in the Kieffer Lab at the University of British Columbia by Drs. Jia Zhao and Shenghui Liang.

This most recent trial sought to significantly increase the amount of insulin produced by leveraging two-to-three times more devices per participant, alongside an updated device design with small perforations to allow for blood vessel ingrowth — a feature aimed at improving survival of the lab-grown cells.

“We now know we can get functional beta cells from stem cells,” said Dr. Timothy Kieffer. “That used to be a big question in a black box. Now, with the results of this trial, we also know the cells are surviving, that they have markers resembling natural beta cells, and, most importantly, we know they can release insulin in a meal-dependent manner. That’s huge.”

Where to next?

Research continues as the teams at Vancouver Coastal Health and the University of British Columbia work toward two goals – increased cell survival and eliminating the need for immunosuppression.

Dr. Timothy Kieffer, alongside researchers at the University of British Columbia.

“As I tell people in my lab, with current gene editing techniques coupled with stem cells, we’re now only limited by our imagination,” said Dr. Timothy Kieffer. “Now we’re thinking about what sorts of things we can be doing to allow these cells to be more robust and withstand the challenges they face when they’re implanted. What tweaks can we make to allow them to better survive and ultimately help patients produce more insulin?”

In another ongoing clinical trial, also funded by SCN, the UBC-VCH team is investigating whether a version of the device containing cells that have been genetically engineered to evade the immune system, using CRISPR gene-editing technology, could eliminate the need for participants to take immunosuppressant drugs alongside the treatment.

“One of the main challenges with diabetes research has always been the need for patients to take anti-rejection drugs so their immune systems do not try to attack the new cells,” said Dr. David Thompson. “Now, in a world first, we are testing genetically engineered cells aimed at eliminating the need for immunosuppression entirely. If successful, this innovative approach could free Canadians from insulin injections, and the debilitating complications of diabetes.”

Since 2016, the Stem Cell Network has invested nearly $10.3M in diabetes research in Canada for 18 research projects, including four clinical trials.

These trials are continuing to recruit participants. People who are interested in participating and want to learn more can contact study coordinator Barbara Allan (barbara.allan@vch.ca).